In our previous article, we introduced ThreadPool through the Executor Framework. This article will discuss the different ways we can create ThreadPool.

The Executors is a factory class, and it has a few static methods ( factory method). Let’s look at them one by one-

Executors.newFixedThreadPool(int nThreads): – this method takes an argument, and with that, we can specify the number of threads we want to have. The threads it creates are called worker Threads. It doesn’t matter how many tasks we put into this ThreadPool; the number of thread will remain the same the whole lifetime of this ThreadPool. If a thread dies for some reason, it will create a new one to keep the number the same.

Executors.newCachedThreadPool(): This ThreadPool create threads on demand. If we add a task to the pool, there is no thread available to execute the task, it creates a new one and adds the pool. The threads are then reused for later use. However, if a thread has not been used for 60 seconds, it is terminated. Usually, this thread pool provides a significant performance boost for short-lived asynchronous tasks.

Executors.newSingleThreadExecutor(): This creates a single worker thread with an unbounded queue. This may sound useless, but it has certain benefits. One of them is if we use it, the programming model stays the same, in case, in future, we want to use another ThreadPool. The changes then become minimal.

Executors.newScheduledThredPool(int corePoolSize): sometimes, we want to keep a task repeating or schedule on a particular time. This ThreadPool allows us to do that. It takes an argument about the number of worker threads it will keep running, even if the ThreadPool is idle. This factory method returns an instance of ScheduledExecutorService, which has a few extra methods that we can use to schedule a job. For example –

import static java.time.temporal.ChronoField.HOUR_OF_DAY;

import static java.time.temporal.ChronoField.MINUTE_OF_HOUR;

import static java.time.temporal.ChronoField.SECOND_OF_MINUTE;

import java.time.LocalTime;

import java.time.format.DateTimeFormatter;

import java.time.format.DateTimeFormatterBuilder;

import java.util.concurrent.Executors;

import java.util.concurrent.ScheduledExecutorService;

import java.util.concurrent.TimeUnit;

public class Playground {

public static void main(String[] args) {

ScheduledExecutorService threadPool = Executors.newScheduledThreadPool(5);

DateTimeFormatter timeFormatter = new DateTimeFormatterBuilder()

.appendValue(HOUR_OF_DAY, 2)

.appendLiteral(':')

.appendValue(MINUTE_OF_HOUR, 2)

.optionalStart()

.appendLiteral(':')

.appendValue(SECOND_OF_MINUTE, 2)

.toFormatter();

threadPool.scheduleAtFixedRate(() -> {

System.out.print(LocalTime.now().format(timeFormatter) + "r");

}, 1000, 1000, TimeUnit.MILLISECONDS);

}

}

The above code will print time, and it would look like a digital watch and it will keep running until we stop it. We used the scheduleAtFixedRate() method, which takes a task as its first argument, and then it takes another two integer arguments, initial delay and period, and the unit of time. It has several other methods, which deserve a complete article only for it. So stay tuned; perhaps in the future one, I will dig deep into it.

Executors.newWorkStealingPool(): java 8 introduced this new ThreadPool, and it uses a particular framework called Fork/Join framework. This one also deserves a complete article, so that I will discuss it later.

Now that we have found a few ways to create our ThreadPool, how do I submit our tasks and get them done?

We have already seen that we can just put a runnable and then submit it to the pool. This works in most cases; however, sometimes, we want to get a result after executing a piece of code. We can get a result in two ways from a ThreadPool. They are through the Callable and the Future interface. Let’s discuss them one by one.

Callable:

The interface looks like this.

public interface Callable {

V call() throws Exception;

}

It is also a functional interface like Runnable; the only difference is that it can return a result and throw exceptions.

Let’s see an example –

import java.util.HashMap;

import java.util.Map;

import java.util.concurrent.Callable;

import java.util.concurrent.ExecutorService;

import java.util.concurrent.Executors;

import java.util.concurrent.Future;

public class Playground {

final static Map cache = new HashMap<>(

Map.of(0, 0L, 1, 1L)

);

public static void main(String[] args) {

ExecutorService threadPool = Executors.newCachedThreadPool();

Future fibonacciNumber = threadPool.submit(new Callable() {

@Override

public Long call() throws Exception {

return fibonacci(50);

}

});

}

private static Long fibonacci(int n) {

return cache.computeIfAbsent(n,

x -> fibonacci(x - 1) + fibonacci(x - 2));

}

}

In the above code, we submitted a job to calculate the 50th Fibonacci number. To submit the job, we have used the callable interface. Since the interface is a functional interface, we can also use a lambda expression.

Future fibonacciNumber = threadPool.submit(() -> fibonacci(50));

But look, it returns the result wrapped with another interface, Future. Let’s talk about it.

Future:

It has several methods:

public interface Future{ boolean cancel(boolean mayInterruptIfRunning); boolean isCancelled(); boolean isDone(); V get() throws InterruptedException, ExecutionException; V get(long timeout, TimeUnit unit) throws InterruptedException, ExecutionException, TimeoutException; }

However, we usually use the get() and isDone() methods for most of the use cases. The idea is that when we submit a task through Callable, it immediately returns a Future. The Future will hold the result when it’s done, not immediately. That means, when we get the reference of the future, the work may not be done yet. We can check that using the isDone() method. We get the result using the get() method. We have to keep in mind that the get() method is blocking operation. The get() method is called from the thread and will be blocked until the result is computed.

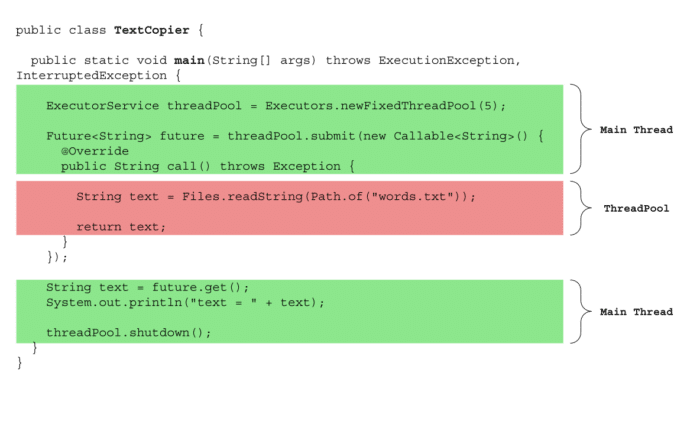

If you look at the image, the main thread executes the green parts. A worker thread from the ThreadPool runs the area with pink colour. It turns out we call the get() method from the main thread. Thus, the main thread will be blocked until we get the result.

Shutting down the ThreadPool

One important thing, once we have done with the ThreadPool, we must shut down the ThreadPool. There are two methods for doing that – shutdown() and shutdownNow();

The shutdown() method tells the ThreadPool that we are not supposed to take any more tasks, and once the existing tasks are done, terminate. On the other hand, the shutdownNow() method terminates the ThreadPool immediately, even if some tasks are still being executed.

I hope this article gives you a glips of how we can use ThreadPool in java.

That’s all for today, cheers!

The post Java Thread Programming (Part 12) appeared first on foojay.

NLJUG – Nederlandse Java User Group NLJUG – de Nederlandse Java User Group – is opgericht in 2003. De NLJUG verenigt software ontwikkelaars, architecten, ICT managers, studenten, new media developers en haar businesspartners met algemene interesse in alle aspecten van Java Technology.

NLJUG – Nederlandse Java User Group NLJUG – de Nederlandse Java User Group – is opgericht in 2003. De NLJUG verenigt software ontwikkelaars, architecten, ICT managers, studenten, new media developers en haar businesspartners met algemene interesse in alle aspecten van Java Technology.